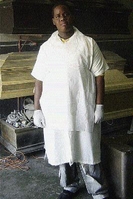

Miguel Irving, the young Tivoli Gardens High School graduate, stands in front of some of the coffins made at Jones Funeral Home and Supplies. - Photo by Paul Williams

Miguel Irving wanted to be a doctor, but when he left Tivoli Gardens High School last year, he realised he wasn't on the path to achieving that dream.

Unhappy with Irving staying at home, his mother approached Michael Jones of Jones Funeral Home and Supplies and asked him to offer her son a job.

Jones made it clear to her that he had no money to pay Irving; moreover, it wasn't a pretty job. He also told her that Irving would have to face an acid test. The 'test' came later when he came face to face with a corpse that was in an advanced stage of decomposition. Jones expected the teenager to run.

What a man brave

"When I step inside, I hear the door close. I was looking not to see him," Jones told The Gleaner. "When I look, him close the door and was smiling, him want him gloves, him ready ... and him jump into it. Mi say, What a man brave!"

But Irving, 18, `has no other option than to be brave. Living in a community where life is not as easy as Sunday morning, his mettle has to be undaunted. With his plans of a career in medicine derailed, he explained that the final-care industry was the closest thing to working with the human body. The advantage over a medical doctor is compelling: There are no fatal mistakes.

"Mi always worry that when I am working on a (live) body, he can die, but when I am working on a dead one, him done dead already," said the trainee Dr Death.

That's why he didn't bolt from the morgue when he was introduced to the decomposing body. "It's something that I love, that I really want to do ... . At first, I believed I would drop down or vomit, but then I said, 'Simple thing that'," he said.

Irving stomached the removal of organs by workers and even helped to hold the bag into which the entrails were put. When he went home that night, he slept like a log. No nightmares, no paranoia.

Mother credited

Irving credits his mother as the main person who prevented him from falling through the cracks. When his uncle, who was a gunman, was killed, his mother became distraught.

"Mi mother say she didn't want that for we. When him dead for a month straight, mi mother couldn't eat, couldn't sleep. Every day she bawl. Say she didn't want that happen to we, and she nuh want we tek coke neither. So it's really mi mother, father too," he said.

Now the youth, who is now trained in many areas of funeral care, hopes to own his piece of the death industry in the future.

"From I was going to basic school, because I am big in body, people always a call me the boss ... . Nobody can say, 'Miguel, mek we go round the road and go do this'," said Irving. "But I don't boss around people and I don't allow people to boss me around."

paul.williams@gleanerjm.com