Dr. Marshall Hall

For some time now, a virtual consensus has emerged about what ails our economy and the endgame requirements for achieving sustainable growth of at least five per cent per year. The key endgame factors are:

The national debt as a percentage of gross domestic product must be reduced.

Tax revenues must be increased to ser-vice the debt and meet the required recurrent and capital expenditure of the Government.

Complementing the increase in tax revenues must be a reduction in interest rates to both the public and private sector.

Crime and corruption must be reduced.

The key growth sectors of tourism and agriculture, and to a lesser degree manufacturing, must be appropriately nurtured.

Any strategy to achieve the endgame will inevitably generate its own set of problems. Which groups will bear the burden of increased taxes? Will increased taxes discourage investment? How does interest-rate reduction square with holding the exchange rate and low inflation? Does the fight against crime and corruption require a reduction in the rights of the citizenry? Despite the consensus on the endgame factors, agreement quickly falls away with each proposal on how to actually achieve them.

Trust

A social partnership among which the key players are the Government, Opposition, workers/unions, the private sector and non-governmental organisations has been seen, by successive governments from as far back as 1996, as the answer to reach agreement on the policies and strategies to achieve the endgame. All parties would agree on a set of conditions, such as wage and salary restraint, a commitment to increase investment, acceptance of the need for tax reform leading to increased tax revenues, and acceptable unemployment targets.

The end result would be an agreement on certain critical performance variables, such as unemployment, inflation and the rate of exchange. With a social-partnership agreement in place, the Government would have achieved societal approval from the key players to introduce the 'correct' fiscal and monetary measures without rabid partisanship attacking every proposal. This strategy has worked in some countries, the most notable being Ireland.

When the People's National Party (PNP) formed the Government, they repeatedly tried without success to forge a social partnership. The key signatories to a social partnership have, to no avail, sat through many meetings and conferences and travelled abroad to learn first-hand how a real partnership can be established.

Last year, the prime minister himself signalled his desire to reach a social partnership and again, despite apparent support from all parties, an agreement has failed to emerge.

Jamaica has remained steadfast in the belief that a social partnership is needed but has steadfastly demonstrated that no agreement is likely to be achieved. None of the key players trusts each other and each quietly, and on occasion stridently, accuses the others of not being willing to put anything meaningful on the table. Along the way, there have been one or two notable memoranda of understanding, but these were at best enlightened self-interest in the traditional union-management rivalry. Is our distrust of each other too deep for meaningful signed social partnership?

The Success Alternative

We do unite in times of major catastrophes or outstanding sporting successes. On those occasions, we take for granted our oneness and demonstrate that we understand that we are indeed our brother's keeper. We work together to rebuild after hurricanes and we smite our individual and collective chests and revel in the individual successes of our sports or musical heroes. The catastrophe or success is clear to all and there is little bickering about the reality of the event.

With both unemployment and the deficit moving in the same negative direction, the Government has found it necessary to seek an agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). In preparation for the IMF submission, it has had to forget about a social partnership as a pre-condition and has introduced a tax package that managed to provoke the ire of almost everybody.

The Government must find a way to get broad support for its policies. We may never achieve a full social partnership or agreement on all of the strategies, but most of us must feel that we are moving in the right direction, even as some scream that the pace is too slow and that there are better options. A vision shared and accepted by most is a minimum requirement for a workable democracy, where the path to the end game requires policies that in the short run will reduce the purchasing power of the majority of households. Because there is no social-partnership agreement, we need successful societal interventions that, like in catastrophes or sporting and musical successes, emphasise our oneness and our understanding that we share a common destiny.

Success Suggestions

The prime minister and the minister of finance, among others, have told us that many who should pay taxes are simply not on the tax rolls. I have not been able to get any estimates of the numbers evading tax, but from the statements of the authorities, I assume that the number is in the thousands.

For each 1,000 tax cheats not on the tax rolls with average taxable income of $2 million, the total taxable income is $2 billion. Tax revenues inclusive of NIS and NHT and Education Tax from only a thousand such cheats would amount to at least $600 million. If we were to add 1,500 tax evaders, with an average taxable income of $2 million, to the tax rolls, the increase in revenue would be greater than the anticipated tax revenue from the GCT on electricity. If this were achieved, the populace would in unison shout, 'Finally!', with the self-belief that we can win out over corruption and increase our tax revenues by improved collection.

The 'feel-good effect' of widening the tax net would be virtually universal. To achieve this, I suggest that most of the cadre of existing tax collectors be told to focus for a three-month period on adding relatively high income-tax cheats to the tax rolls. The future of this approach should be evaluated at the end of the first three-month push. Simultaneous with the push to get additional taxpayers on the tax rolls should be a push to also get non-GCT-paying businesses on the tax rolls. With some 40 per cent of the economy in the informal sector, there must be many businesses, with revenues above the $3 million GCT free threshold, that are evading the GCT net. A systematic approach sector by sector, business district by business district, must be undertaken to rope in these evaders.

These tax-collection measures are not a substitute for genuine tax reform that broadens the tax net, looks rationally at property tax. The recent announcement that Jamaica ranks almost at the bottom among some 170 countries in unnecessary tax bureaucracy is simply unacceptable. This feeds through to companies having to devote too many resources to do the tax computations and the tax returns. It is simply absurd for Jamaica, correctly in my view, to want to collect more taxes and bizarrely at the same time be at the bottom of the pile in both tax collection and unnecessary tax bureaucracy.

The drive to increase tax revenues by targeting the cheats is sensible in and of itself. I am, however, suggesting that this type of major success in the national economic arena will indicate to all that our leaders are committed to the required transformational change necessary to achieve the endgame factors. This commitment will begin to foster the unity of purpose that is the reason for social partnerships. It is this unity of purpose that will begin to forge a workable understanding and agreement on the key strategies and policies that must be followed to produce the end game of growth, crime reduction and a manageable deficit.

Improving tax collection is but one of the many achievable policies whose success will engender unity and an acceptance that change policies, though painful, can work. A critical requirement for these high-profile successful interventions is that they must be corruption free with a short payback period.

The minister of agriculture's drive to ensure the wide use of greenhouse techno-logy and his push for a large cassava industry is an example of an intervention that, if widely successful, will engender unity and demonstrate that real change is possible.

Another potential area of relatively quick, but meaningful success is in the reduction of traffic accidents and the general indiscipline on our roads. Success here can be both quick and cost effective and will surely spin off into the collective psyche that tough decisions can produce good results.

The adage that nothing succeeds like success is applicable to achieving a successful and workable social-partnership agreement-type outcome.

Dr Marshall Hall is a former CEO and professor. Feedback may be sent to columns@gleanerjm.com.

Elaine Palmer-Wallace (left), taxpayer service officer at the King Street Collectorate, assists a taxpayer during the Special Taxpayer Service Programme in 2006. - Andrew Smith/Photography Editor

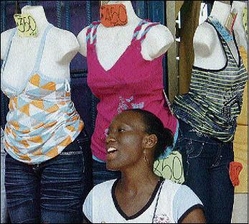

A roadside vendor peddles clothes on Orange Street in downtown Kingston in December 2008. Many small-business operators like her are not within the tax net. - Norman Grindley/chief Photographer