The importance of Peter Tosh and Bunny Livingston to Marley's ascendancy

The following is the second instalment of a two-part feature on the importance of Peter Tosh and Bunny Livingston to the rise of Bob Marley as an international reggae icon. Part one was carried yesterday.

The Wailers were a musically cohesive unit on all angles. Together, texture, vocal flexibility, timbre, sense of musicality, thematic interest, kinship and vision was reflected in their overall sound and informed their spirituality and aesthetic concepts. Qualities of voice notwithstanding, they all were fine singers for a number of other reasons. Bob Marley's haunting beauty, with its hint of hurt and urgent optimism; Peter Tosh's bold enunciation, his texture and clear diction, natural range between baritone and tenor, coupled with his ability to swoop between ranges without effort, sometimes interchanging with Bunny Livingston whose honey-flavoured tenor revealed none of the artificiality that accompanies those achieved by way of falsetto, which was the property of singers not as endowed.

Double consciousness

The group's overall sense of timing, harmony, nuance, call and response, shouts, grunts, hollers, innovation, and downright daring, conveyed both regret and celebration that resulted in emotional counterpoint that played to W.E.B. Dubois' point about double consciousness. Melancholy and cheerfulness, unreserved and unrequited love, optimism and despair, imbibed lyrics that danced or moaned over driving ska, rocksteady and reggae rhythms that are the quintessential expression of celebration.

The outcome was a mixture of delight and sorrow, a combination of tragedy and exhalation, sensibilities that are as emblematic of the blues as they are testimony to Albert Ayler's maxim: "Music is the healing force of the universe." That Marley's genius would embody many of these attributes is indeed testimony to his ability to harvest from the epic poetry that exemplifies The Wailers as a group.

Too many songs with political meaning that have become hits had messages that were lost on listeners, because they lacked empathic intimacy.

Individually and collectively, Tosh, Marley and Livingston represented the varied approaches to black cultural production; preaching, oratory, and singing, playing with and shaping words, phrases and rhythms, narrowing the boundaries between singing and testifying, entertaining and educating, stretching and constricting syllables, signifying and troping, often vocalising phrases as though the lyric ricocheted from drums with fresh syncopation and punctuation to the poetic sensibility that informs the text. In the hands of any other group, then or now, the sensibilities that imbue the gems that exemplify the original Wailers would have been missing and the music would not have had the same resonance.

For those reasons, this trio remains the zenith of distinction and the essence of greatness; they define the idea of interplay, in-group collaboration, and reflect the result of collective and individual commercial and artistic successes.

The success of later editions of The Wailers, and also the individual successes each member of the trio attained, owes much to the efforts of their own innovations and pioneering adventures. Yet, through no doing of his, Marley has been the recipient of all the accolades, and as his stature has ascended to that of demigod, the contributions of Tosh and Livingston, more and more, have been erased, remains overlooked and is all but forgotten, leaving the impression that on his own, the achievements were all Marley's.

Take for instance Vinette Price's eye-catching headline from a recent article of hers - 'Marley's 'Catch A Fire' makes it to Grammy Hall of Fame' [Sunday Herald: Class, December 13-19, 2009. Page 18]. Here is a recording first released in 1972 under the name of the title The Wailers: Catch A Fire. A few years later it was being marketed as Bob Marley and The Wailers. Now we are lead to believe Catch A Fire is Marley's sole effort. Here is the first sentence of Prices article: "Bob Marley's Catch A Fire release is finally considered timeless by the Recording Academy, the music specialists responsible for the Grammy Awards."

Misleading pronouncements

Notwithstanding that the last line of the second-to-last paragraph of the article refers to the recording as Bob Marley and The Wailers, such pronouncements are misleading and serves to diminish the contribution made by Tosh and Livingston to this fine recording. Indeed, this first international release by the group, also showcases in addition to Marley, both Tosh and Livingston as lead singers, composers and instrumentalists - in the case of Tosh on no less than three instruments. Drawing attention to the collaborative effort, here is a quote from the online encyclopedia Wikipedia regarding Catch A Fire's impact.

"The recording's ... socially aware lyrics and militant tone surprised many listeners, but others were attracted to songwriters Marley and Peter Tosh's confrontational subjects and optimistic view of a future free from oppression." [Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org accessed 10/1/2010]. And as Jimmy Guterman writes: "Marley's not the only lead singer; this is very much a group, as proved again in the nearly equal follow-up, Burnin', which featured more well-known songs like Get Up, Stand Up, and I Shot the Sheriff ... (N)ever were Marley, Tosh, and Livingston more impressive than when they worked together." [Jimmy Guterman, The Best Rock 'n' Roll Records of All Time, 1992. http://www.superseventies.com accessed 10/1/2010]. Continuing to place emphasis on group contribution and interplay, Michael Woodsworth adds:

"Not only was this the first reggae album to penetrate the rock market, it was also Marley's key collaboration with fellow Wailers' founders Peter Tosh and Bunny Livingston. ... Backed by the ... squeaky-clean upbeats of Tosh's guitar, the trio laid out the range of their vocal ability, broadcasting their militant message in rich harmony. Tosh's forceful 400 Years and the wailing, menacing Slave Driver recall slavery's oppressive historical legacy.

Marley sings lead on all save two of the tracks, but Catch A Fire is definitely the work of a band - one bursting with hunger and creative energy." [Michael Woodsworth, 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die, 2005. http://www.superseventies.com accessed 10/1/2010].

So, if you are among the multitudes who only think of The Wailers as the post Catch A Fire (1972) and Burning (1973) group led by the incomparable Marley, or one likely to be confused by ill-informed or wilful statements that diminish the contribution of Tosh and Livingston to the legacy of The Wailers and Marley's acclaim, you are urged to immerse yourself in the music of the aggregation's formative years to understand just why they alone among Jamaican groups could have become trendsetters on the competitive international scene as early as they did. To better understand and appreciate the contributions of these two outstanding original Wailers, one must be willing to go beyond the Island recordings and engage in the early recordings for Clement 'Coxone' Dodd, Beverley's, Lee Perry, and on their own Wail 'N' Soul 'M' label.

The two-disc compilation, Bob Marley and The Wailers - One Love At Studio One 1964-1966, (1991, Heartbeat Records) is perhaps the best place to start. It collects 41-tracks that brings together the A and B sides of a range of singles, many alternate takes and previously unissued sides to give a most compre-hensive overview of this amazingly authentic group, their singularity and the contributions of its two overlooked, if not underrated members. Livingston and Tosh are featured here not only as harmony singers, the greatest in my estimation in vernacular and idiomatic terms, but they are also placed centrestage as lead singers, and in Tosh's case, musician (guitar, melodica and keyboard), and are also recognised for the compositions they contributed. It is important to know, as well, that unlike many groups that fell apart after their lead singer (in reference to the Wailers, two lead singers, first Junior Braithwaite to Chicago and then Marley to Delaware) migrated, The Wailers held together and continued having success with massive hits. Ironically, songs recorded prior to his return are today routinely accredited to Marley in spite of his absence when they were recorded.

Since his death, a carefully designed and executed kind of slanted promotion has given the impression that Marley was the Wailers, and that Tosh and Livingston were secondary participants, utilised as backup vocalists. But nothing is further from the truth. In fact, in an interview with Neville Willoughby, Marley stated his commitment to the group by subtly addressing the skewed publicity that undermined the trio's democracy.

"I am committed to The Wailers. Fi some reason dem seh, Bob Marley and The Wailers. I neva tell anyone fe seh dat."

Reconfigured Wailers

The success of Bob Marley and The Wailers, the reconfigured group, beginning with the release of Natty Dread (1974), could not have been achieved without the combined efforts of these three titans of early Jamaican popular music. They, above all others, are responsible for modernist approaches to how they and the music would become internationally marketable, and to deny any of the three the honour of recognition for his efforts is to deceive, discredit and defame.

Combining idiomatic influences, philosophy, social consciousness, style (both visual and auditory), attitude, originality and most importantly, authenticity, the contribution of the original Wailers (Bob, Bunny and Peter) to sonic and stylistic Afro-modernity parallels The Beatles' in terms of the British quartet's influence on modern pop and Duke Ellington, Miles Davis and Picasso's ability to be simultaneously fashionable and profoundly artful.

Social inequity

Like Picasso was able to achieve with his tour de force paintings, 'Guernica' [1937], which captured and reflected the shock to Franco's acts of terror during the Spanish Civil War, and 'Massacre in Korea' [1951], based on the slaughter of Korean civilians by US forces in 1950, The Wailers were equally up to the task of addressing institutional and social inequity and malevolence through their compositions. Albums such as Catch a Fire and Burning, both by The Wailers, and Blackheart Man [1976], Exodus [1977] and Equal Rights [1977] by Livingston, Marley and Tosh respectively, can be acclaimed as socio-political statements without succumbing to commerciality at the expense of creativity, artistic integrity, or the complexity that characterises the vital force of humanity. And as much as Marley is its most recognised member, both Tosh and Livingston must be acknowledged as the next two most important and influential group members whose collaborative willingness engendered the greatness of The Wailers, and helped to stimulate Marley to become the creative genius that we celebrate. Elevating Marley and denying Tosh and Livingston their rightful credits, kudos and the respect due them is a travesty. If we really regard our musical history, respect truth and consider the importance of The Wailers and its best known member, Marley, among Jamaica's uttermost gifts to the world, let us as historians, publicists and cultural custodians make it our duty to challenge those who wish to rewrite history by distorting facts. Let us commit to re-empower these two unsung Wailers, Peter Tosh and Bunny Livingston. Such truth, democracy and attention to injustice, is what the individual members personified and the original Wailers exemplified.

Herbie Miller is the director/curator of the Jamaica Music Museum at the Institute of Jamaica and is a cultural historian with specialised interest in slave culture, Caribbean identity and ethnomusicology. He can be contacted at herbimill@aol.com.

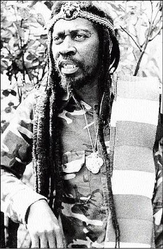

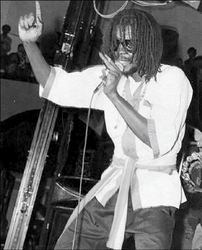

( L - R ) Bunny Wailer, Peter Tosh